I still vividly remember the first time I encountered the portraits of world leaders by David Platon. It was at Photokina in 2012 — then the world’s largest photography trade fair, held every two years in the vast halls of the Kölner Messe in Cologne. Hall after hall packed with photography products, from the latest camera bodies and lenses to lighting systems, software, and accessories. For any photographer, it was like stepping into a very well-lit candy store.

My primary focus at Photokina was always: technology. New tools, new techniques — the things that help us do our work better. That meant I often skipped the photo exhibitions. Artistic inspiration is important, of course, but there are plenty of other opportunities to see great photography, both online and in museums or books. But that year, on a whim, I decided to have a quick look at the exhibitions.

That quick look turned into a moment that quite literally stopped me in my tracks.

I walked into the exhibition hall, and immediately felt as if my feet were nailed to the floor. Surrounding me were enormous black-and-white portraits of world leaders — displayed with such clarity, power, and presence that I couldn’t look away. Barack Obama, George W. Bush, Angela Merkel, Vladimir Putin, Muammar Khaddafi, Nelson Mandela, to name but a few — each rendered in stark, dramatic black and white, each personality caught so magnificently.

It was here that I first discovered the work of portrait photographer David Platon — and I was instantly a fan. If I showed you his portraits, chances are you’d recognise them immediately. His image of Putin, in particular, has become iconic — used in protests around the world. What always amazed me is that these leaders, with carefully curated public images, allowed themselves to be photographed like that. And that, I believe, is the mark of a great portrait photographer: the ability to connect with the subject, to disarm them, and to capture something authentic — sometimes even vulnerable — in just a few moments.

Fast Forward to 2025: A Different Kind of World Leader

Jump ahead to 2025, and I find myself in the studio with a young creative who is building his artistic identity and taking his ambitions seriously. He’s a musician, a performer, and very intentional about how he presents himself. And for his portrait photography, he relies on someone he knows rather well — his dad.

That’s right — the artist in question is my son, Judah.

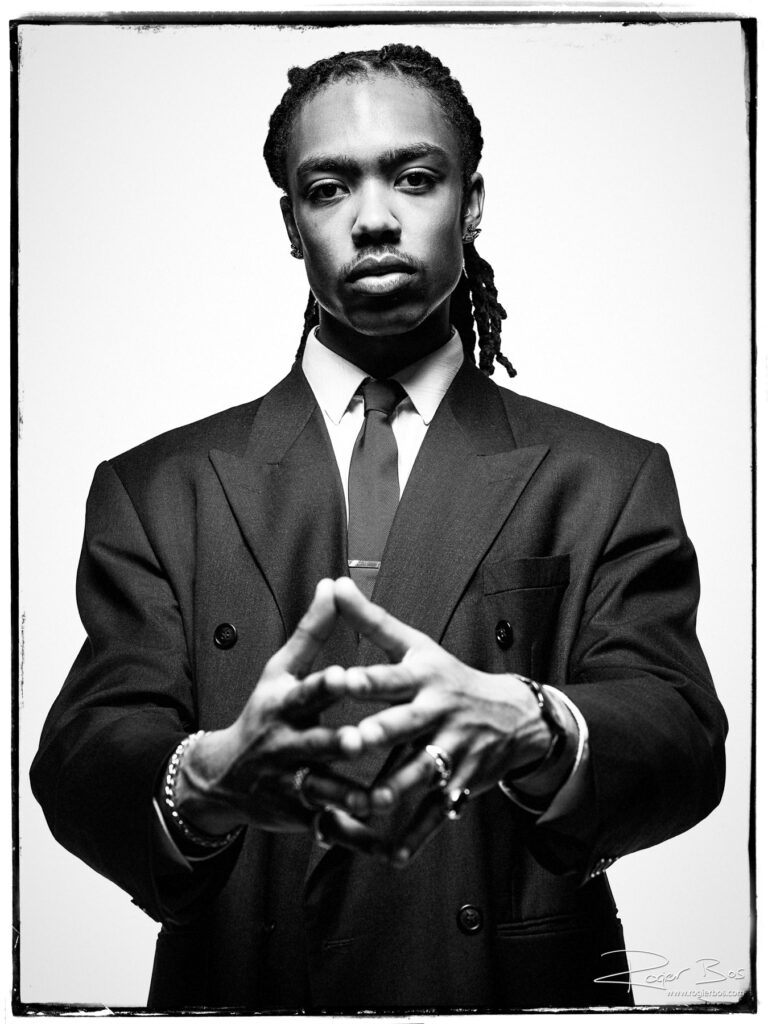

As a father, it brings me great joy to see my son develop his talents and pursue his passions. As a photographer, it’s a pleasure to contribute to that process. Judah typically arrives at the studio with a clear concept. He has an exceptional eye for fashion and detail — always dressed with care and precision. And then he gives me room to work creatively within his vision. It’s a collaboration that works well for both of us.

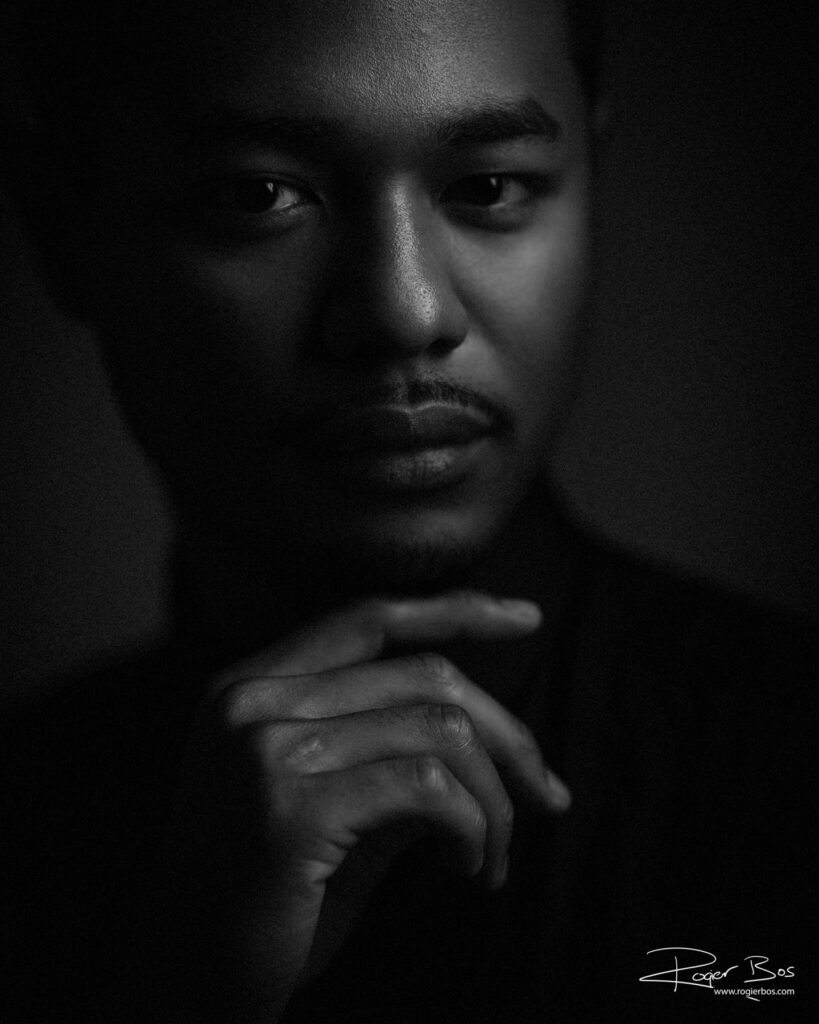

At our most recent shoot, somewhere between adjusting lights and reviewing captures on screen, something unexpected happened. I suddenly saw it: the composition, the contrast, the point of view — the image reminded me of David Platon’s work. Black-and-white. Clean framing. A low perspective. That unmistakable, serious tone.

When I showed Judah the photo, he said, “This reminds me of pictures I’ve seen of… someone famous. I don’t know the name.” I pulled up some of Platon’s portraits, and as soon as he saw them, he said: “Yes! That’s exactly who I was thinking of.”

It was a gratifying moment. And it sparked an idea.

A Creative Experiment Begins

I regularly initiate personal projects to keep myself creatively engaged and to experiment with new techniques. This encounter with Platon’s style felt like the perfect springboard for one of those projects. The idea: could I create a series of portraits in the style of David Platon?

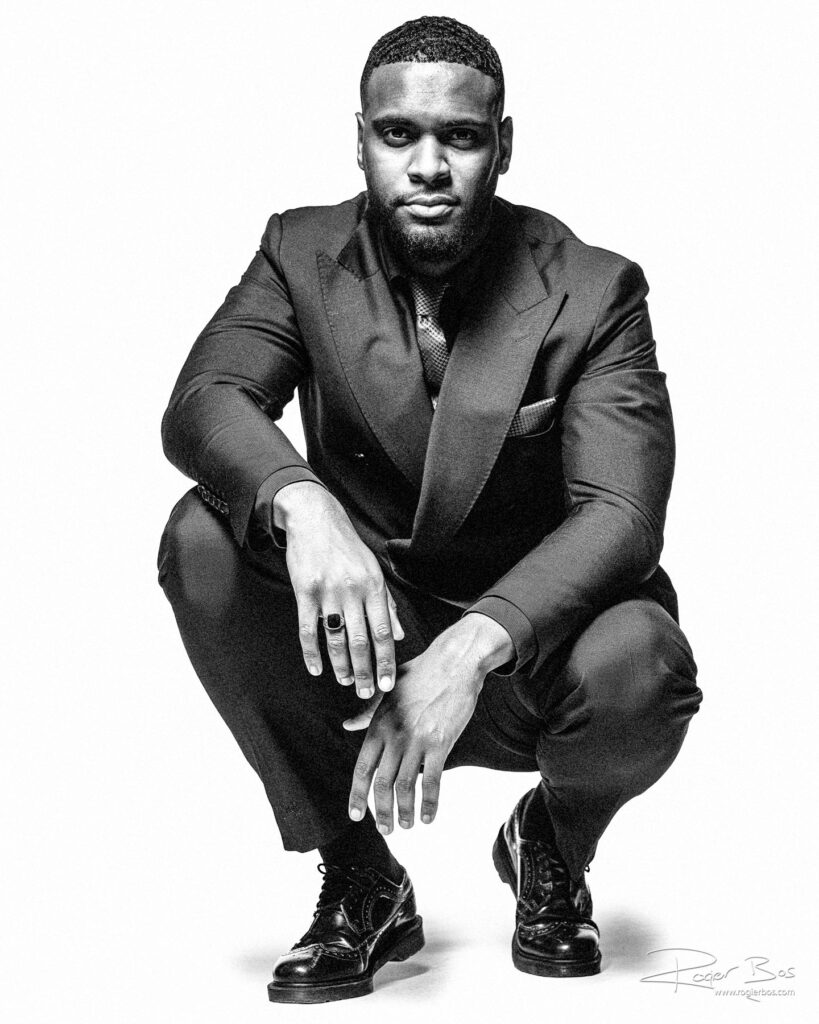

Judah enthusiastically joined the effort. He recruited five of his friends — all young men with strong features and excellent fashion sense. They came to the studio, each prepared with a carefully chosen outfit. I had an hour with each of them, and we structured the session accordingly: thirty minutes attempting Platon-style portraits, and thirty minutes to explore something of my own.

Studying the Master

Before the shoot, I took time to study Platon’s work carefully. I looked through dozens (if not hundreds) of his images, and watched interviews and behind-the-scenes footage where he discusses his process. Unsurprisingly, there isn’t much available — truly great photographers don’t share their secrets too freely. But I did learn a few key things that I tried to implement in my own way.

Here’s what I observed, and how I translated it into my own portrait photography setup:

- White seamless background

Platon uses a clean, white backdrop that disappears entirely from attention. This was simple enough to replicate in the studio. - Medium format camera with wide-angle lens

Platon shoots with a Hasselblad system. I work with the Fujifilm GFX100S — also medium format — and recently acquired the 55mm f/1.7 lens. While not identical, this combination gave me a similar look: wide enough for presence, but with the depth and resolution that medium format provides. - Overhead lighting

His lighting is simple but deliberate: a single light source directly above the lens, often through a shoot-through umbrella. It casts shadows downward, sculpting the face and enhancing the intensity of expression. - Dark edge fall-off

A subtle but important detail: where Rembrandt lighting creates a light edge on the subject, Platon often uses techniques to darken the perimeter. I achieved this by positioning black V-flats on either side of the subject to absorb light and create that subtle dark rim. - Low perspective

Platon consistently photographs his subjects from a slightly lower angle. This adds presence, elevates the subject’s posture, and — notably — brings the hands into play. - Hands as focal points

Most portrait photographers (myself included) tend to hide the hands unless they serve a clear purpose. Platon does the opposite. Hands often dominate the frame — expressive, honest, even confrontational. I encouraged my subjects to keep their hands visible and active in the frame. With each pose I carefully observed the hands: what story were they telling?

These were the primary stylistic choices I focused on in recreating a Platon-like atmosphere in my studio.

Results and Reflections

So — how did it turn out?

Below you’ll find a selection of the images from this project. I’m pleased with the results. The portraits are strong and carry a seriousness and weight that I rarely pursue in my commercial work. That alone makes the project worthwhile.

But in terms of actually imitating Platon’s style? I would say it was at best a partial success.

There’s something I’m missing — and I can’t quite put my finger on it. It is tehncical or or psychological? Of course my models are not world leaders, and as such do not have such strongly developed personas. Is it that? Or was I just unsuccesful in solliciting from them the gravity, depth, or intimacy they have within them? It’s clear that Platon’s genius isn’t just in his setup or camera settings, but in how he connects with his subjects. He’s able to draw something out of them, often in just a few minutes, that gives the image a lasting emotional impact.

That’s a humbling realization — and also an invitation to keep growing.

So if you’re familiar with Platon’s portrait photography and you notice what’s missing in my version, I would truly value your insights. Where did I almost succeed — and where did I fall short?

And David — if, on the off-chance you Google yourself and find this post (though I doubt you are that vain) — your feedback would be more than welcome. Even a single line would make my week. 😁

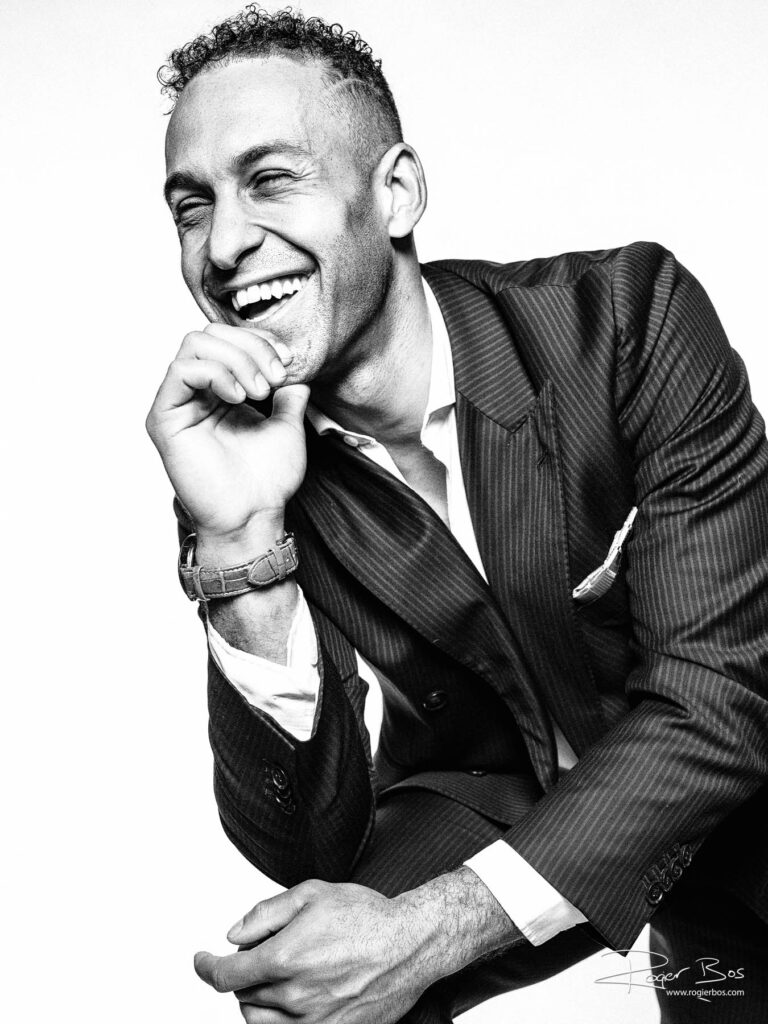

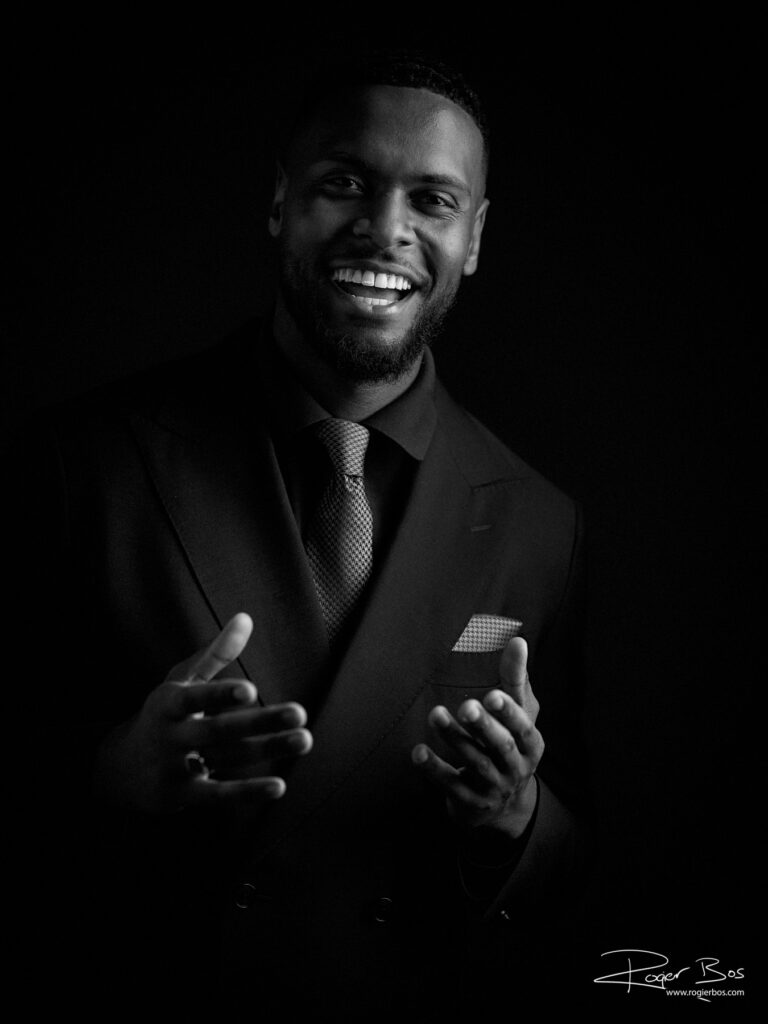

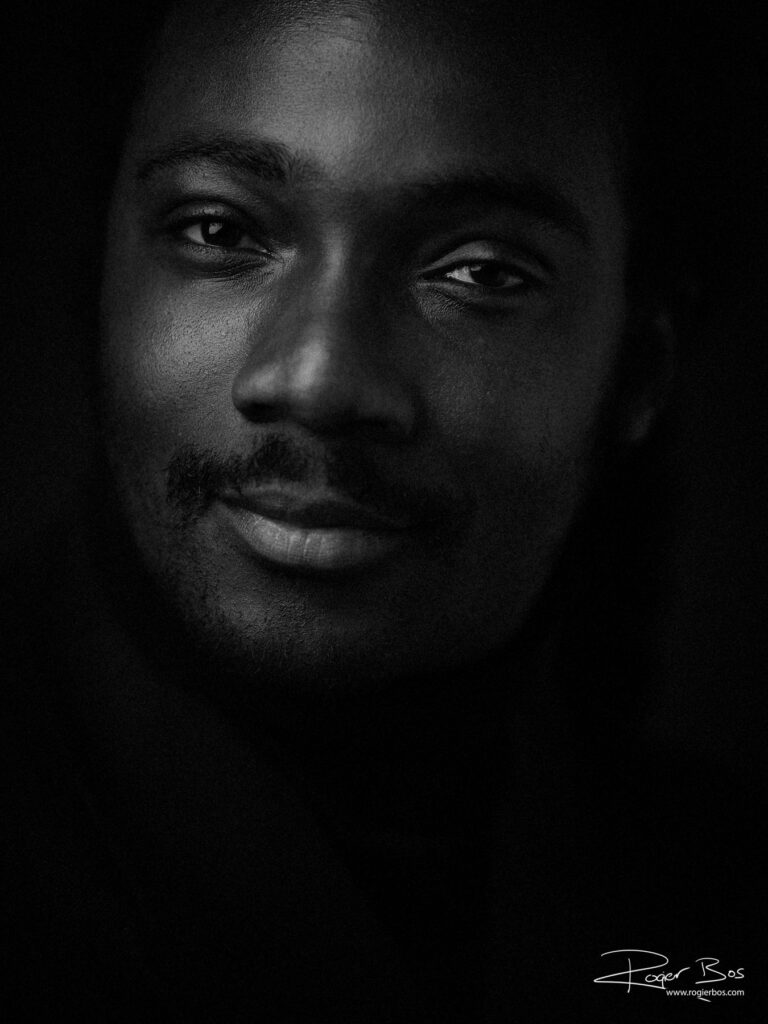

The Other Half: Dark Portraits

These five models were shot in the time of one Saturday, an hour aeach. If that seems short to you, Platon himself regularly only gets a few minutes with his subjects. They are, after all, very important people who are very busy with being very important.

So I gave myself half an hour with each model to imitate Platon. My rationale was simple: if I couldn’t do it in half an hour, extending the time wasn’t going to increase my chances of success.

I reserved the second half of our session for a different creative direction. After exploring the white background, we switched to a black one. This part of the session wasn’t inspired by Platon, but by a question I’ve been asking myself lately: how dark can I make a portrait while still preserving clarity and emotional connection?

As a portrait photographer, I often work with dark backgrounds — but I’ve noticed I tend to play it safe. These sessions gave me the opportunity to push those boundaries. The resulting images are indeed quite dark, and intentionally so. I was interested in where the edge lies: when does dramatic lighting become too moody? When do shadows start to overpower the expression?

Portrait photography: a skill you continually develop

Again, this was part of the learning experience. These images may not appeal to everyone, but they help me refine my instincts and experiment with tone, depth, and simplicity.

If you have thoughts, reactions, or suggestions — especially if you’re familiar with Platon’s work — I’d love to hear them.

And if you’re simply here to enjoy the portraits, thank you for taking the time.

About the author

Rogier Bos is a professional photographer, living in Rotterdam, and working in the Netherlands and beyond. He specialises in corporate photography and does a lot of portrait photography, in his office settings, in industrial locations, and in his studio.